Culture and Continuity

Navigating Identity Across the SWANA Region

Across South West Asia and North Africa, culture is not an accessory to identity – it is its foundation. The SWANA region, with its multiplicity of languages, traditions and rituals, has always held culture as a source of resistance, survival and remembrance. But this vast stretch of geography has also been subject to division. The legacy of colonialism is not just visible in political borders, but in ruptured histories and fractured solidarities. Yet culture endures, not simply as heritage, but as a living, moving force that binds across imposed lines.

Even the term SWANA itself, South West Asia and North Africa, is a political intervention. It attempts to replace the colonial legacy of 'Middle East', a label that centres Europe and erases local geographies. But the term remains contested. Some argue we should reclaim and redefine existing labels, while others prefer to abandon them entirely. What is clear is that naming is never neutral. It reflects who holds the power to define and who is being defined.

The term 'Middle East' in particular has long troubled many in the region. It positions our geography in relation to Europe, rather than as its own centre. Some resist it entirely, while others argue for reappropriation and pragmatic use in international settings. This debate itself reflects a deeper struggle over voice and agency, who defines us, and on what terms.

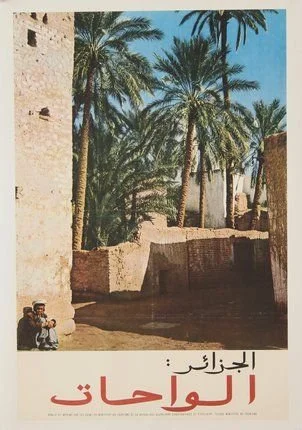

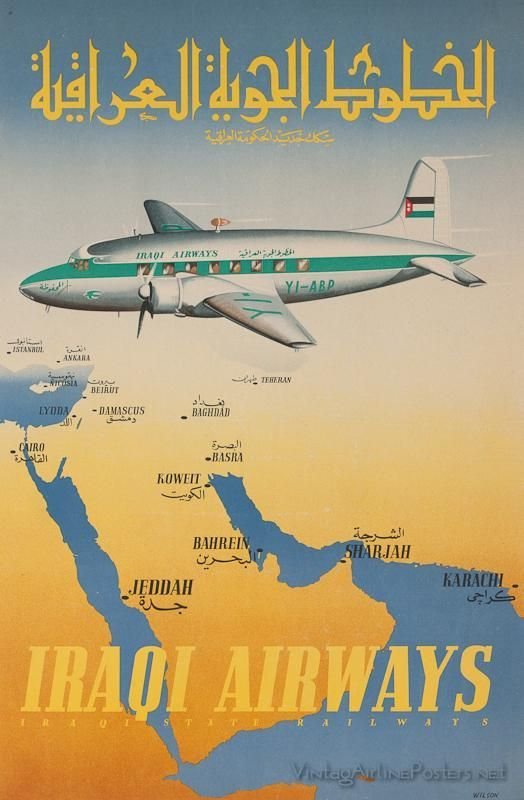

What we call the SWANA region today has always been diverse: Tamazight poetry from North Africa, Kurdish music in the Levant, Yemeni architecture, Egyptian cinema and Nubian rituals. But imperialism and its aftermath have treated this diversity in two contradictory ways, it has fragmented and yet homogenised us. While colonial powers imposed arbitrary national borders and pitted groups against one another, orientalist narratives painted us all with one brush. We were either desert dwellers, oil barons or fundamentalists. The texture of our everyday realities was erased.

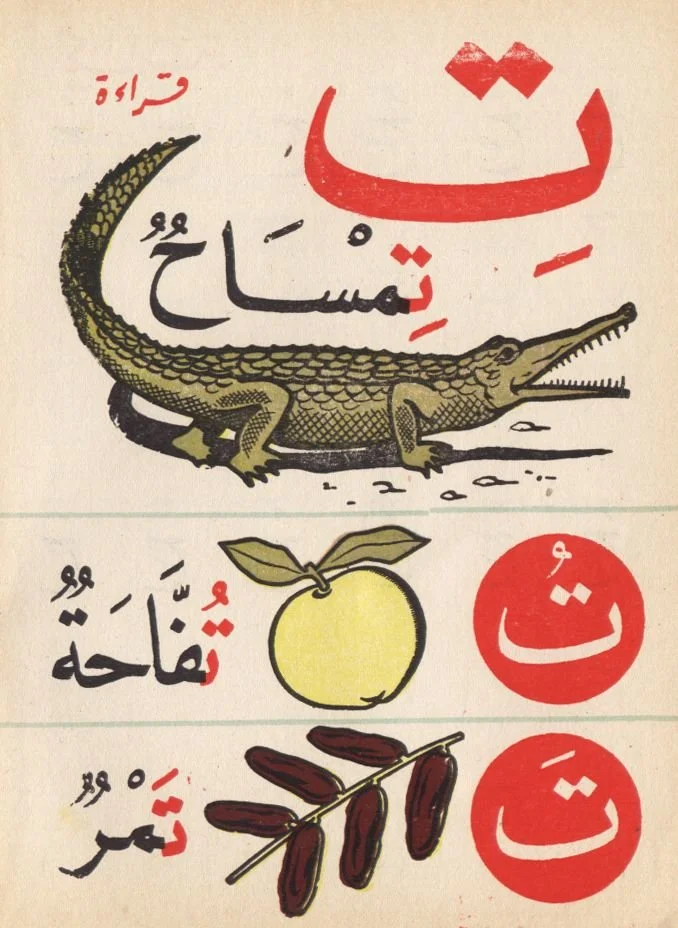

Yet those textures are precisely what culture preserves. The Palestinian thobe is embroidered with village specific motifs. Algerian rai music tells stories of migration, defiance and love. Egyptian cinema, once the beating heart of Arab pop culture, shaped aesthetics across the region, from Beirut to Baghdad. These cultural forms are more than expressive outlets. They are archives. They carry what formal history books have often excluded.

Anthropologists have long argued that culture should be seen as lived practice, as a way people navigate, adapt to and push back against their social conditions. In the SWANA region, this is especially true. Take, for instance, the dabke. On the surface, a communal dance. But in refugee camps in Lebanon and Palestine, it has become a ritual of return, a way to reclaim space and memory. Or consider the music of artists like Rizan Said or Omar Souleyman, whose work channels rural sounds into global platforms, resisting both marginalisation and commodification.

Language too is a site of cultural survival. Arabic, Persian, Kurdish, Amazigh, Turkish – these are not only languages of communication but of worldview. Colonial education systems and post colonial nation building often undermined linguistic plurality, pushing centralised, often elite, versions of language. But poets, rappers and playwrights have refused this erasure. Today, the rise of regional dialects in literature and music marks a resurgence in linguistic pride.

What unites the SWANA region, despite its pluralism, is a shared experience of loss and endurance. Whether through war, migration or authoritarian rule, people have turned to culture to make sense of pain and to imagine alternative futures. The artist who paints the wreckage of Aleppo, the filmmaker who documents diaspora in Marseille, the poet who writes of exile from Khartoum – each is participating in a regional conversation about belonging, identity and power.

The digital age has accelerated this. Artists and collectives now collaborate across borders, bypassing state censorship and forming new solidarities. Pages like @muslimgirl or @kabreetmag highlight underground work, while platforms like Liya aim to centralise cultural memory as a tool of resistance. These are not just aesthetic projects, they are political interventions.

Still, we must be cautious. Cultural revival can be coopted. Nationalist regimes often repackage heritage to serve their narratives, while global markets commodify it for consumption. The challenge is to protect the subversive potential of culture, to keep it tethered to the communities and struggles it emerges from.

To celebrate SWANA culture is to resist forgetting. It is to insist that identity is not given by the state, but shaped through song, stitching, story and sound. It is also to recognise our interconnectedness, not in spite of our differences, but through them. There is deep variety in how we cook, sing, mourn and tell stories. But these differences are not divisions, they are part of a broader cultural ecology that makes the region so textured and so rich. What many in the West see as one bloc is, in reality, a constellation of interconnected cultures, each distinct but historically entangled.

As we look forward, culture offers more than nostalgia. It offers blueprints. In an era of displacement, repression and erasure, it is culture, not politics, that is often our first and last refuge.