Erasure by Design

Cultural Resistance and the Zionist Project in Palestine

The Palestinian struggle is too often narrated solely through the lens of geopolitics. But culture — songs, fabrics, foods, rhythms, names — has long been a central battlefield in the Zionist project. This is not an accidental erasure. It is structured, calculated, and central to a settler-colonial logic that seeks not only to displace people, but to erase their existence from history and imagination. To speak of Palestinian culture is to enter a terrain of resistance.

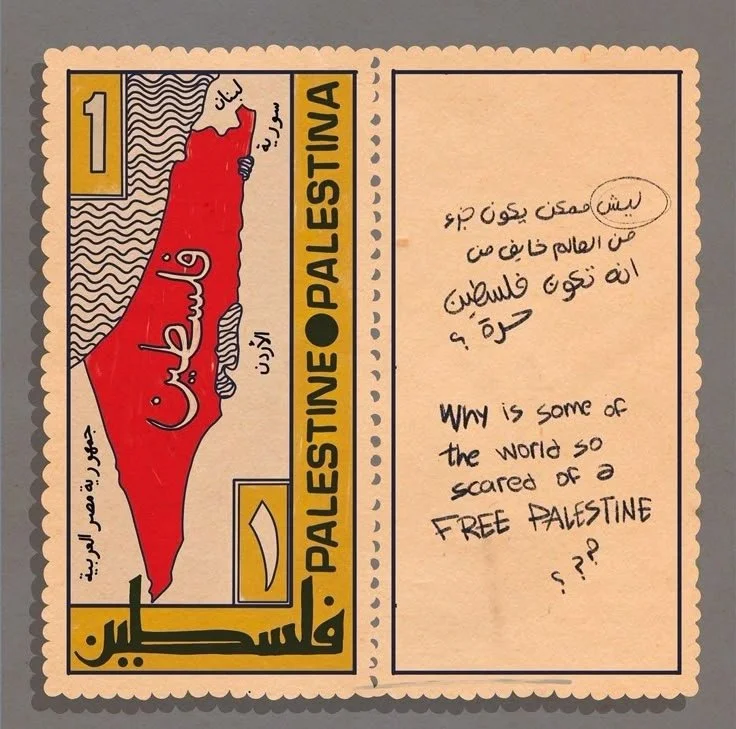

Since the early 20th century, Zionist narratives have attempted to paint Palestine as a land "without a people for a people without a land". This foundational myth necessitated the silencing of any trace of Palestinian culture. Villages were destroyed not just for strategic or demographic reasons, but to wipe out continuity. Olive trees uprooted, mosques and churches bulldozed, and Arabic street names Hebraicised. Cultural erasure is embedded in architecture, geography, and daily life.

One of the most visible battlegrounds is clothing. The Palestinian thobe, rich with regional embroidery motifs, has been misrepresented or appropriated in fashion circles as either Israeli or generic "Middle Eastern" style. In 2018, an Israeli contestant in a Eurovision promotional video wore a dress styled on a traditional Palestinian pattern. In response, Palestinian women launched the #MyThobeMyIdentity campaign, reclaiming ownership through visibility.

Music has also been targeted. Traditional Palestinian songs and rhythms have either been dismissed as backwards or absorbed into Israeli folklore without attribution. Yet music remains a site of vibrant resistance. From revolutionary anthems sung by exile choirs in the 1970s to contemporary trap and rap artists like Shabjdeed and Daboor, Palestinian artists continue to build sonic worlds that defy borders and occupation.

Cinema too has become a powerful mode of cultural defiance. Filmmakers like Elia Suleiman, Annemarie Jacir, and Farah Nabulsi use film not only to represent Palestinian realities, but to preserve memory. In a context where oral histories are under siege, cinema becomes an archive. The very act of filming life under occupation, of documenting the mundane alongside the violent, is a refusal to be erased.

Zionist cultural policies also extend into archaeology and education. Palestinian historical sites are often mislabelled or presented within frameworks that favour Israeli narratives. Curricula in occupied areas are censored. Books are banned. Even poetry — such as the work of Mahmoud Darwish — has been viewed as a threat to the Israeli state.

And yet, in spite of this, Palestinian culture persists. In embroidery circles, dabke troupes, underground art collectives and Instagram pages, Palestinians are recording and reviving what colonial violence has tried to obliterate. This revival is not nostalgia. It is strategic, it is political and it is an insistence on being.

In the diaspora, too, cultural expression is growing. From Berlin to Santiago, Palestinian artists are using murals, spoken word, fashion, and cooking as forms of solidarity and survival. Culture provides a way to build transnational alliances, to speak across language barriers, and to assert existence even when displaced.

But the international community must also confront its role. Western media, academia, and the art world continue to frame Palestinian culture as marginal, dangerous, or irrelevant, unless it fits into acceptable narratives. Institutions that claim to celebrate diversity cannot remain neutral in the face of cultural erasure.

To fight for Palestinian culture is not simply to showcase its beauty. It is to acknowledge the violent systems trying to erase it, and to commit to opposing those systems. This includes not only occupation, but also the global complicity that sustains it.

Cultural survival is a form of resistance. And resistance, in Palestine, is always cultural.